Through the Looking Glass at Newfields

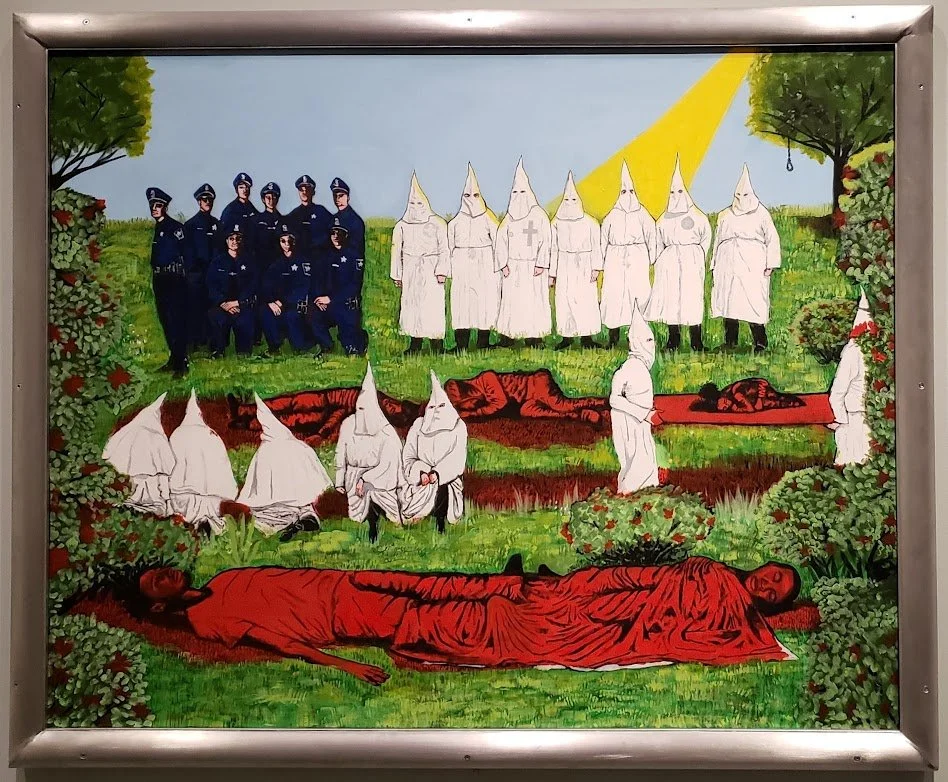

“Big White System” by Kyng Rhodes

I visited the American Galleries at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields on June 27. This was my first visit since the galleries had reopened in late May. A significant refresh took place during the time the galleries were closed to the public. This reorganization incorporated the contributions of five residents of the Indianapolis community dubbed the Looking Glass Alliance (LGA). In coordination with Newfields staff, the LGA created content for the galleries to hang alongside well-known works from the Museum collection.

The purpose, broadly speaking, is to begin a conversation.

More specifically, according to the Museum, the modus operandi of Work in Progress: Conversations about American Art is to use “the idea of a looking glass to turn upside down the white, heteronormative interpretations of art and the American mythos that have been traditionally been communicated in museums.” In future updates to the permanent collection, the curators hope to incorporate, for example, works by indigenous artists made before and after European colonization. Per the wall text, the current gallery reorganization is limited in scope by the fact that the Museum’s holdings of American art consist largely of work made in the US from the late 18th century forward. (Such representation-focused reorganizations of permanent exhibition spaces are taking place at some other prominent museums, such as the Brooklyn Museum.)

There is, nevertheless, a lot of change to absorb in terms of curation and new content. It will not please everyone. Consider the 2022 painting “Big White System” by the Looking Glass Alliance’s Kyng Rhodes, evoking the American flag in his prominent use of red, white and blue colors. Here you see (white) Klansmen in white, Blacks laying on the ground in pools of red blood, and blue-uniformed policemen, alongside a portrait from the Museum collection titled “Little Brown Girl,” depicting a girl named Nellie Henderson, painted by Indianapolis artist John Wesley Hardrick in 1927. Rhodes’ painting, per the wall text, attempts to answer the question, “What was the reality of Nellie’s experiences—beyond the painted backdrop?”

And as the wall text also notes, at least one-quarter of white men in Indianapolis were members of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.They targeted not only African Americans but also Jews, Catholics, and immigrants from eastern and southern Europe for abuse. By deploying the colors of the American flag in his painting, Rhodes suggests that the freedom that the flag stood for was only for freedom for white people, and the freedom (for them) to lynch Blacks with impunity. The wall text notes Rhodes “was a little brown boy in the 2000s” who grew up to find that the struggle for racial justice is not yet over.

This struggle is referenced, at least obliquely, in the work of Nasreen Khan who has two paintings in this exhibition. One of the paintings, titled “Anchor, Baby” depicts Kali, a Hindu goddess of tremendous power with a baby at her breast. As the goddess is depicted breathing fire, it’s not irrelevant conceptually that Khan used pyrography as a method of composition. According to the wall text, “This piece addresses the artist’s experience as an immigrant to America and the journey of giving birth and becoming a mother while living in an inhospitable foreign country.” Khan herself is Filipino/Afghan raised in Senegal and Indonesia, an immigrant to this country, who is raising her son in the Haughville neighborhood of Indianapolis. It is an intriguing juxtaposition, I think, for the artist to depict herself as a goddess who in the Hindu pantheon holds power over time itself while her title evokes the vulnerability that many immigrants feel coming to the US. That is to say, “anchor baby” has become a derisive label in right wing media and politics for children of undocumented immigrants who, under the 14th amendment, receive birthright citizenship.

“Anchor, Baby” by Nasreen Khan

Perhaps a new immigrant might feel compelled to follow the advice suggested by the title of Khan’s other painting in this exhibition, a canvas painted entirely in white, titled “Keep Your Head Down.” Khan means, with this white canvas, to indicate the lack of work in the Newfields collection by people of color, be they immigrants or indigenous peoples. Per the wall text, “Sometimes what isn’t included in the art of the day tells a lot more than what does get included.”

One of the contributions of the LGA’s architectural historian and scholar Jordan Ryan is to make the point that what is included, in terms of a work’s subject matter, can be discussed through the looking glass, as it were, of economic inequality. Consider the painting “Streetlight” from Constance Coleman Richardson, which she painted in 1930. It depicts a nighttime scene, with figures on sidewalks lit by street lamps, in Indy’s Meridian-Kessler neighborhood. But at first glance, you may be thinking less of its sociological implications and more about how it engages you artistically. In fact, you can find text online, on the Newfields site, that compares Richardson’s impressionist-influenced style to that of Edward Hopper. It also notes Richardson’s interest in conveying essences rather than concrete detail.

The new wall text, however, dispenses with any discussion of art technique or style. It states that the painting “reflects a deeper story about disinvestment in urban neighborhoods” and points out the fact that under the practice of redlining, the Meridian-Kessler neighborhood was rated “best” while neighborhoods with large Black populations immediately to the south were rated “definitely declining” or “hazardous.” This rating of neighborhoods effectively denied the people who lived in those areas home loans, and thus largely prevented them from transferring wealth from one generation to another. Bringing in discussions of economic disparity into the American Galleries in such a bold way might not please everyone. But it can certainly act as a conversation starter.

Likewise Tatjana Rebelle’s contribution to the exhibit, her poetry, focuses on entrenched racial injustice. The juxtaposition of her poetry with a portrait of Dr. Lewis D. Lyons by Barton Stone, a work completed around 1855, is meant to highlight the subject’s status in society. This was a time, per the wall text, when Black Americans’ status in society was restricted not only by slavery in the American South, but by laws like Article XIII, passed by a majority of Indiana voters, preventing new Black settlement in the state. (The article was declared unconstitutional in 1866 by the Indiana Supreme Court.)

Rebelle’s poem, titled “What is Freedom?” contains the following lines: Freedom of movement is a true gift/One that we often take for granted/One our ancestors were denied. One hundred and sixty-seven years later the Indiana General Assembly considered Senate Bill 386, which would have likely restricted the ability of teachers to mention Article XIII in their classrooms, under the guise of preventing the teaching of Critical Race Theory. (The bill passed the Senate, died in the House.) The bill is likely to be considered again in some form or other. So are bills aimed at the undocumented immigrant population in the state of Indiana, given that both chambers of the Indiana General Assembly are controlled by a Republican supermajority. This population, according to the latest data from the American Immigration Council, is 101,773, and has paid $187.8 million in state and federal taxes.

A new addition to the American galleries, a new acquisition, speaks to the national debate about immigration. It is photograph and video of a 2011 performance piece “Borrando la Frontera” (Erasing the Border) by Mexican-born, San Francisco-based artist Ana Teresa Fernández, in which she painted a 12-foot long stretch of the border fence separating the U.S. from Mexico (on the Tijuana side), a performance which she accomplished while wearing a black cocktail dress and pumps. The color of the paint was light blue. As a result of her work, at certain times of the day, viewers at the beach in Tijuana in the early-to-mid 2010s were able to entertain the illusion that they could walk right through the fence.

“Erasing the Border” by Ana Teresa Fernández on Mexican side of border, as it appeared in 2015. The man in the white cap is a coach for the Club Tijuana soccer team drilling one of his players, who is outside the frame.

photo by Dan Grossman

This piece speaks directly to the question “Are national boundaries arbitrary?” raised in the wall text for Nasreen Khan’s “Keep You Head Down.” In fact, most of the southwestern US, until 1848, had Mexico City as its capital. Westward expansion and the desire for Texas independence fueled the Mexican-American War, after which Mexico lost half of its territory. The boundaries between the two countries were redrawn. Many Southwestern residents trace their ancestry to Mexico, have family on both sides of the current border, and speak Spanish—a language that was spoken on the American continent a century before English gained a foothold on the eastern seaboard. There is a growing movement of Mexican-American activists, in fact, who claim the territories lost to the US as their own, dubbing them Aztlán. Although theirs is more of an idea expressed in literature and art than an actual move towards secession, it has the benefit of being grounded in historical reality. My attempt to answer the aforementioned question, then, is to suggest that the US national boundaries may be fixed, at least for the time being, but that doesn’t make them fair, just, or practicable.

The end goal of increasing representation in the American Galleries, while a practicable goal over the long haul, will be challenging given the provenance of much of the Museum’s collection. But the idea has come a long way since I first toured the American Galleries with Associate Curator of American Art Dr. Kelli Morgan in 2019, after she had made some preliminary rotations in the galleries.

A mural in Chicano Park, in the Barrio Logan neighborhood of San Diego, depicting the territory of Aztlán.

Photo by Dan Grossman

During our walk, we stopped in front of the portrait “George Washington at Princeton” by Charles Wilson Peale (and his nephew, Charles Peale Polk) and described Peale’s founding of the Philadelphia Museum, which later was known as Peale’s American Museum, in 1786.

She described Peale’s museum as a place for him to “put all of his cool stuff in, to invite all of [his] friends to come and look at all of [his] cool stuff.” Then she went onto say the following: “There's no way that we can have the conversations that we're trying to have now about diversity, or widening the audiences or museum outreach without acknowledging that was never the point in the first place.”

I had no way of knowing how fraught Morgan’s tenure at Newfields would be, or that she would exit the institution a year later, after claiming in a letter that she widely shared that that Newfields was “consistently failing “its BIPOC staff, allies, and local communities” and, as an institution, was “toxic”. I had no way of knowing that in February, 2021, museum director Charles Venable, who had hired Morgan, would resign after he included the phrase “core, white art audiences” in a job description for Museum director and the resulting controversy.

Under the current directorship of Colette Pierce Burnette, who is the first Black woman to lead the museum since its founding in 1883, the Museum has seen innovations in the direction of increasing representation for minority artists including the group exhibition We. The Culture: Works by the Eighteen Art Collective, the artists who created the Black Lives Matter Street Mural.

(Walking through the “We the Culture” exhibition, I was struck by its diversity in terms of different styles and mediums, the boldness of the conceptual content of the works, and the sheer talent of the Collective members.)

But not everyone in the world of museum administration is on board with diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Consider the June 29 article in ArtNews titled “American Revolution Museum in Philadelphia Faces Pushback from Historians for Hosting ‘Extremist’ Group.”

That is, on June 29, the Philadelphia museum hosted the opening reception for the Joyful Warriors National Summit for the advocacy group Moms for Liberty. Among the events’ speakers: Donald Trump, Ron DeSantis, and Nikki Haley.

You may have heard of the group Moms for Liberty. The Hamilton County chapter made national news last week by quoting Hitler in their June newsletter.

Paige Miller, chair of Moms for Liberty, Hamilton County Chapter, and Tony Kinnett, executive director of The Chalkboard Review Photo by Dan Grossman

Per the article, “While Moms for Liberty describes itself as an organization that enables caregivers of children to ‘defend their parental rights,’ the group has agitated for bans on material dealing with slavery, racism, and the oppression of LGBTQ+ communities in schools.”

It’s a fair bet that no Joyful Noise summit will take place at Newfields, at least under Burnette’s leadership. But it’s only a matter of time before this Moms group and/or their allies weigh in on the curatorial changes taking place in Newfields and like-minded institutions. Perhaps their rallying cry will be Make Museums Great Again.

For Newfields, like other museums that are restructuring for the 21st century, change is ongoing. A clear endpoint might never be reached. There may be debates, arguments, and misunderstandings along the way. But the conversation the Museum is having with local artists and other members of the Indianapolis community is real, and is happening now.

Note: the audio-visual display for LGA member Bobby Young was not functioning at the time of my visit.