Mark Latta confronts housing inequality and redlining in Indianapolis

Mark Latta addressing students, faculty, and community members at Marian University on December 9.

Housing inequality in Indianapolis is an ongoing concern for Mark Latta, director of community engagement at Marian University. It is a problem that he contends is tied to structural inequality in the United States.

But before such problems can be remedied, they have to be addressed and Latta has spent considerable time and energy in this endeavor.

On Thursday, Dec. 15, Latta will lead “A Conversation about Evictions in Indy” at Rooster’s Kitchen 888 Mass Ave. It’s a conversation that will include Public Action Writing Students from Marian University, and Qualitative Methods in Geography students from IU Bloomington.

Latta led a discussion on a similar issue at Marian University on Dec. 9. His talk centered on the legacy in Indianapolis of redlining, which is the practice of denying home loans, or other services, in neighborhoods with substantial numbers of minorities and/or low-income residents.

While this was a practice that was prevalent in the United States, beginning in the 1930s and ending in the 1960s, the legacy of the practice is still with us, Latta said.

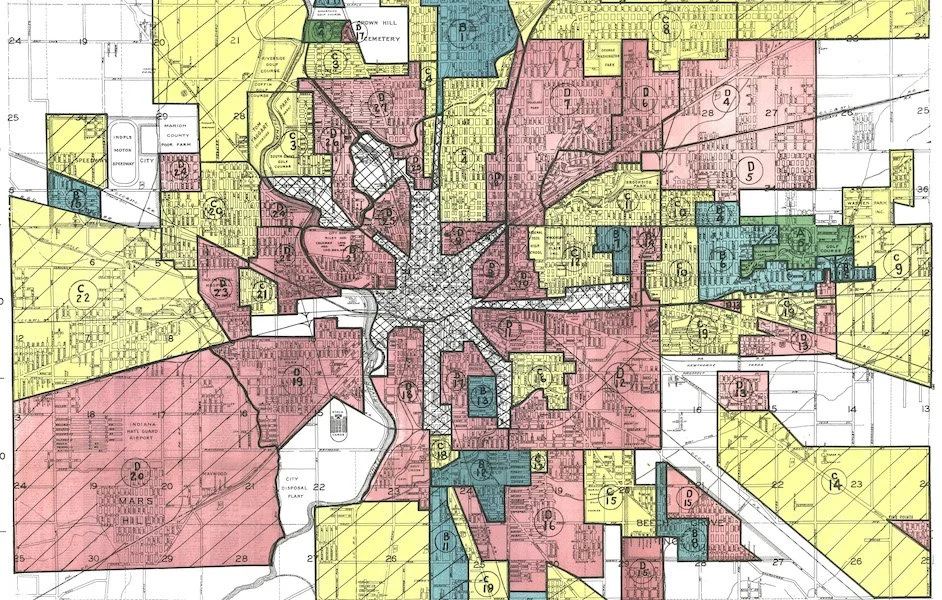

Redlined map of Indianapolis neighborhoods: Courtesy of the National Archives

“I think it's a really important topic of conversation for us to understand and to know that it’s something that people are still grappling with and that we are also in the midst of this grappling,” he said.

Centering his discussion on the denial of home loans to African Americans in Indianapolis, he began his talk with some historical background. When the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was born with the National Housing Act of 1934, he said, it was tasked with allowing more Americans to buy homes. Originally, the FHA approached this task in a colorblind way.

“And when that happened,” Latta said, “there was quite a bit of reaction on the ground. People started hearing that everybody would get mortgages, that they could qualify in addition to mortgages that also included a whole slate of public housing programs. This produced a reaction among the populace … And so in response to people preferring segregated communities, the FHA developed a set of guidelines. They developed a manual that basically said that it was risky, explicitly higher risk, to back mortgage loans made to houses located in predominantly Black areas.”

The process of redlining in Indianapolis echoed the practice that also took place in major urban areas across the United States. If you look at a redlining map of Indianapolis, you will see areas of red converging on Center Township: not coincidentally these were all areas with high numbers of African American residents.

The urban core of Center Township is mostly red, and then as you move outwards you find areas coded in yellow, then green and blue, and the color-coated areas were labeled A, B, C, D, based on desirability, with A (blue) being the most desirable and D (red) being the least.

“FHA would not back any mortgage in D; they would routinely deny most mortgages in C which will be yellow,” Latta said. “So you really wanted to try to find in order to have your mortgage backed by FHA, you really wanted blue or green areas.”

Latta also detailed how I-65 and I-70 were routed through predominantly redlined areas, compounding the effects of the practice by displacing entire communities.

In effect, the urban planners who created the redlining maps also mapped out future areas of housing inequality, of income inequality, and of health disparities. That is, if you overlay individual maps exposing these problems—one on top of another—there is virtually a one-to-one match, but it all began with the practice of redlining. By taking away the most common way of accessing and generating wealth—owning a home—redlining denied Indianapolis residents of color the ability to pass down wealth to their children and these denials created a domino effect down through the generations.

“That also leads to lack of access to services,” said Latta, “The redlining map could become the map for essentially any type of desert: food, literacy. This is how we arrived at this place in the United States where the zip code is the single greatest predictor of health outcomes, educational attainment, economic mobility, lifetime learning, lifetime earnings, justice involvement, and premature death in the United States. And it all stems from this idea of FHA designating African American neighborhoods as higher risk.”

The legacy of redlining is something that you can see quite clearly in Indianapolis today, where 38th Street forms a border, of sorts, between wealthy neighborhoods like Meridian-Kessler to the north and the economically-disadvantaged communities to the south.

“Historically, that red line, the northern border, ended at 38th Street,” said Latta. “So if you drive around the neighborhoods of Marian and then you drive around the neighborhood of Butler, one of the things you're seeing is the historical implications of redlining.”